Environmental Conservation in the Turks and Caicos

The Turks and Caicos is home to an incredible marine and terrestrial environment, which is the primary driver of the tourism and luxury development market. Unfortunately, ongoing development has begun to greatly impact certain areas, especially on the island of Providenciales.

Threatened Fauna and Flora

As a small and somewhat isolated archipelago, the Turks and Caicos is home to many types of native and unique plants and animals, some of which are only found in the Turks and Caicos, and a broader number that is only found on a few of the southern Bahamian islands and the Turks and Caicos. Simply due to the limited extant of these plants and animals, many are considered endangered or threatened.

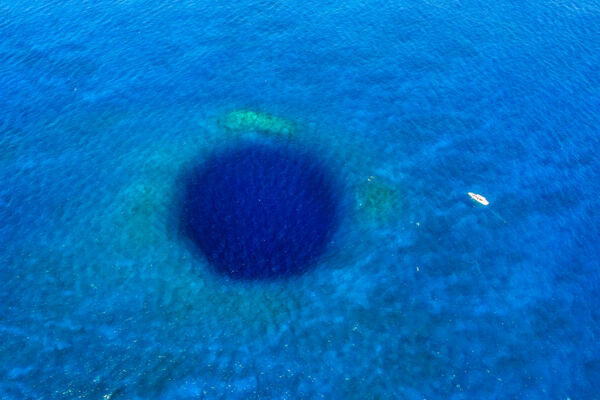

Stony Coral Tissue Loss

A foremost threat to the environment of the Turks and Caicos and the broader tropical Atlantic is the stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD), a disease that has been observed throughout the Turks and Caicos and attacks many types of large, hard corals. This disease is thought to be a bacterium, and the only known effective response requires localized treatment, which makes it incredibly difficult and expensive to respond to.

Stony coral tissue loss disease is common at popular dive sites, and has been observed at some of the most remote locations in the Turks and Caicos. The disease was first identified near Florida in 2014, and its rapid expansion is extremely concerning. Turks and Caicos Reef Fund has been leading the response to the issue in the Turks and Caicos.

Turks and Caicos Islands Rock Iguana

Probably the best-known endemic terrestrial animal of the Turks and Caicos is the Turks and Caicos Islands rock iguana (Cyclura carinata). This large and docile lizard is found on some of the mid-sized and smaller cays in the Turks and Caicos. Once considered ‘critically endangered’, long ongoing conservation efforts have recently resulted in an IUCN conservation status change to ‘endangered’.

Conservation efforts have largely consisted of invasive mammal removal from key habitats (Little Water Cay, Half Moon Bay, Water Cay, Pine Cay, and Ambergris Cay), reintroduction of iguanas to certain uninhabited cays, and more recently, the removal of invasive casuarina trees at Half Moon Bay to allow natural iguana habitats and food sources to regrow.

Smaller Reptiles

The Turks and Caicos has its share of endemic, unique, and threatened reptiles. As the islands are small and isolated, many of our reptiles are found on only a few islands in the world. Another consideration is the lack of population and habitat data, which is limited to the extent that the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) doesn’t even offer conservation status on most of the reptiles native to the Turks and Caicos. The two large (compared to our blind snakes!) boas in the Turks and Caicos would both be likely to be considered endangered due to their limited numbers and habitat, as well as some of our geckos. The Turks and Caicos curly-tailed lizard (Leiocephalus psammodromus) has been given the conservation status of ‘vulnerable’.

The Turks Island boa (Chilabothrus chrysogaster), which is often referred to locally as the rainbow boa, is likely found on 10-12 islands in the Turks and Caicos, and the Caicos Island Dwarf Boa (Tropidophis greenwayi), which may be the smallest constricting snake in the world, is possibly only found on 14-20 islands. The boas tend to thrive in and prefer tropical dry forest with a comparatively high canopy, and there is very little such environment in the Turks and Caicos that is either protected as a nature reserve or national park, or is unlikely to be developed in the future.

Conch

The queen conch (Strombus gigas or Lobatus gigas), quintessential to the Turks and Caicos and its culture, is of concern to many environmental and marine conservation groups. It is undeniable that wild conch populations have seen a significant decline, and it is now very uncommon to spot the giant mollusk at any easily-accessible coastal area or beach. Some critics have suggested a far stricter conch fishing season and perhaps limits, yet such actions have not been taken.

One theory is that the Conch Farm, now defunct and abandoned, was artificially raising the numbers of conch in the wild, due to their practices of egg fertilization and saturation of conch in the Leeward Going Through Channel between Providenciales and Mangrove Cay. Conch egg masses have hundreds of thousands of eggs, yet it’s estimated that typically only about one egg from each mass on average reaches maturity in the wild. In a controlled setting, it has been shown that if the fertilized eggs are protected past the larva and metamorphosis stages of the conch life cycle and then released, the survival rate is astronomically higher.

Proposed ideas are that the best and most practical way to raise conch populations in the wild is to strategically release fertilized conch eggs, larva, or post-larva stage conch at locations in the channels between some of the cays and in the Caicos islands, where, if timed right with the tides, there could be efficient distribution over the natural conch habitats in the Caicos Banks.

Birds

The Turks and Caicos is a haven for a wide array of birds, and except for some habitat loss, there isn’t as widespread a threat to birdlife as is the case with other flora and fauna. Poaching and hunting of birds rarely if ever occurs.

An interesting fact is that flamingos may have been the first animal to be protected by law in the Turks and Caicos, having been protected for more than a century.

Lack of Environment Protections Enforcement

One of the greatest problems affecting the environment in the Turks and Caicos is not the lack of legal protections, yet rather the lack of enforcement of the law. Departments in the government tasked with monitoring and enforcement largely ignore the violations with the greatest impact.

There are many examples. Planning guidelines in the Turks and Caicos prohibit corner-to-corner bulldozing, yet the practice is quite common, and in cases done by the government itself. The Planning Department was instilled with the duty of enforcement, yet they largely ignore the issue. Destructive clearing results in the complete loss of habitats supporting thatch palms, orchids, sacred lignum vitae (Guaiacum sanctum) trees, and many more types of threatened flora. Such flora could serve landscaping purposes if builders and developers were given some incentive to preserve them. The damage isn’t constrained to habitat loss. Flooding issues, pollution, and general ugliness are also accompanying outcomes.

Another example of the lack of enforcement was significant flora theft from a nature reserve. Around 2017, hundreds of mature and seeding buccaneer palms (Pseudophoenix sargentii) were stolen from the Frenchman's Creek and Pigeon Pond Nature Reserve on Providenciales. This rare palm is native to the Turks and Caicos and are considered endangered by the state of Florida. The population stolen represented nearly all mature trees on Providenciales, and was significant to the extent of the tree in the Turks and Caicos as they are quite uncommon in the archipelago. The government appears to refuse to take any meaningful action in this case, even after the stolen trees appeared to be located.

Yet another example was illegal bulldozing in the Northwest Point Pond Nature Reserve on Providenciales. Around 2017, a track was cleared through the western side of this sensitive nature reserve, and through blue land crab and bird nesting habitats. The track appeared to lead to a large tract of beachfront land offered for sale. As in the case of the theft of trees, the government appeared to refuse to take any meaningful action.

Another case of environmental destruction in the Turks and Caicos is the Cooper Jack Bay caves on Providenciales. This site was described by geologists as:

“An approximately 4 acre area on the coast and extending inland at Cooper Jack Bay contains a large number of banana holes, small flank margin caves, pit caves, and other karst features that would form an excellent natural preserve to allow the public to see a wide range of karst features, the impact they have on land use, and the impact they make on local ecology.”

Nearly all cave features were bulldozed and filled in 2022.

The unfortunate fact is that many view the government departments tasked with enforcement with distrust and dislike, with beliefs that reports of poaching, environmental damage, and infractions being rarely if ever responded to, and that some small water sports and charter businesses are focused on regarding enforcement.

Deforestation of Native Forest for Charcoal Burning

The Turks and Caicos faces a number of persistent environmental issues, yet a significant one of more recent emergence is the extensive cutting of native forest for charcoal burning, which primarily takes place on the island of Providenciales.

On the remote central western side of Providenciales, roughly 600 acres of native old growth tropical dry forest has been cut, simply to be burnt in kilns for charcoal. This practice is conducted by Haitians, likely illegals, and the finished charcoal is likely both used locally and exported to Haiti in some cases.

Rare hardwood trees such as the sacred lignum vitae (Guaiacum sanctum), West Indian mahogany (Swietenia mahagoni), Jesuit bark (Extosema caribaeum), and nakedwood (Thouinia discolor) are preferred by the charcoal burners over faster growing softwoods due to the quality of coal that their wood produces, which results in trees that are likely over a century old being cut, simply to be burnt.

The cut wood is stacked densely, covered with dirt, clay, and rocks, and then is lit to be burnt slowly over a period of time. Many of these large kiln sites can be seen in the cleared forest spaces. After the charcoal is finished, the kiln is dismantled, the coal is collected, and usually packed into large bags for distribution.

Charcoal burning causes significant and long-lasting damage to the islands, yet the Turks and Caicos Government and its various departments that this issue would be the purview of are unwilling or unable to take any meaningful action to stop the practice.

Lack of Data and Decision Making

A significant concern in the Turks and Caicos is that broad and impactful decisions are often made with a complete lack of data, especially data that justifies the actions taken.

Reductions to Protected Areas

A prime example is the proposed reductions to the Chalk Sound National Park and the Pigeon Pond and Frenchman’s Creek Nature Reserve. The significant reductions were initially guised under the pretext of ‘fixing paper mistakes’ that allowed for residential parcels in the national park to be sold and developed.

It quickly became apparent that the residential properties were a fraction of what was intended to be removed from the nature reserve and national park, and reductions were to include popular attractions such as West Harbour Bluff, more than half of the coastline, and much of the beach in the nature reserve, historical sites, caves, wetlands, and a critical habitat for buccaneer palms (which were subsequently stolen from the nature reserve).

Due to public outcry, the government has continued to stall on any definite action, yet an unnatural pressure appears to continually cause the protected areas reduction issue to be raised with each new administration, despite the overwhelmingly negative feedback from the general public and environmental groups.

Likely due to the public outcry, the government began the process to obtain various impact assessments, which were never initially obtained in the first few rounds of the reduction attempts. Unfortunately, the typical government practice is to select a contractor that historically can have a professional background from a very broad basket of experiences, areas of expertise, and qualifications, regardless of what qualifications and experience are pertinent to the areas of concern. In the case of Pigeon Pond and Frenchman’s Creek, the environment and historical concerns are expansive, and include pre-Columbian historical sites, historical sites from later periods, Karst Process caves which include multiple complex underwater systems that are at the least home to endangered crustaceans, terrestrial terrain that includes a broad representation of Turks and Caicos vegetation and land environments, wetlands of highly-varying salinities, and future likely area uses that include tourism and recreation. It’s simply unlikely and reasonable that a single person or small contractor can offer a complete analysis of the situation.

Invasive Species Control

An ongoing focus of environmental conservation groups is the control of invasive species. The Turks and Caicos, and especially the island of Providenciales, has seen the introduction of a tremendous number of invasive flora and fauna, as well as many plant diseases, including pine tortoise scale, which threatens the Caicos pine (Pinus caribaea var. bahamensis, a subspecies of the Caribbean pine).

There is simply no reasonable expectation of eradicating some of the extant invasive species in the Turks and Caicos, so consequently there is no broad effort, or any effort at all. Some examples include the Cow Bush (Leucaena leucocephala), the common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus), Cuban tree frog (Osteopilus septentrionalis), and the northern curly-tailed lizard (Leiocephalus carinatus). Cow bush tends to outcompete nearly all native flora in disturbed land, and the invasive reptiles displace the local varieties due to their aggression and prolificacy.

Lionfish, a predatory fish from the Indo-Pacific that is now present in the Caribbean and tropical Atlantic, is another example. Found through the waters of the Turks and Caicos, it is legal to spear, yet there are no expectations of control or serious population reductions.

Invasive Mammals

Invasive rats, mice, cats, and dogs are found on all populated main islands in the Turks and Caicos, rats, and mice are extant on many of the cays of any significant size.

Generally, invasive mammal control is limited to cays that have an extant Turks and Caicos Islands rock iguana presence, including Little Water Cay, Half Moon Bay, Water Cay, Pine Cay, and Ambergris Cay.

Green Iguana

The green iguana (Iguana iguana), an invasive menace on many islands in the Caribbean and in Florida, has been spotted in the Turks and Caicos on the islands of Providenciales and Grand Turk. Sightings continue to be occasional, and efforts are being made to trap any sighted on Providenciales to prevent them from becoming established, as the ecological damage the iguanas cause on other islands in the tropical Atlantic has been significant.

Control of the green iguana is largely overseen by the Turks and Caicos National Trust, with assistance from experts from around the world.

Casuarina

Casuarina is an invasive and fast-growing tree species from Australia that are now found throughout the tropical Atlantic. These trees are often the tallest vegetation around, and their ability to grow in high salinity conditions and essentially tolerate ocean water has resulted in them growing on many coastlines in the Turks and Caicos. A rough estimate is that there is about 24 miles (38 km) of coastline in the Turks and Caicos with mid to heavy levels of casuarina saturation.

One protected area that has seen concerning expansion of casuarinas is the Half Moon Bay Lagoon location in the Princess Alexandra National Park. The invasive trees are displacing the native vegetation that support iguanas with ‘dead zones’ of heavy needle ground cover, where other plants can’t grow, and where there is little to no forage for the iguanas. Attempts are being made to remove casuarinas from the area.

Pollution and Littering

The Turks and Caicos has a high tolerance for littering, and practically no enforcement of littering and dumping laws. It’s common to see drivers littering from moving vehicles, especially when stopped at roundabouts. The problem is persistent and present on all developed islands, yet more so on Providenciales and Grand Turk. Local social movements have attempted to remove and reduce littering, yet the problem generally progressively worsens.

Trash collecting in the Turks and Caicos ranges from being provided by the government in certain communities, to being a paid-for service that is provided by private businesses in other areas. All solid waste landfills are owned by the government, and there is no charge to dispose of waste. Despite this fact, refuse is often dumped illegally, often only minutes away from the legal dump sites.

It’s often considered that the lack of enforcement of dumping and litter laws is the root of the problem, and that simply imposing the fines already allowed by law would quickly reduce littering.

Recycling in Turks and Caicos

Recycling efforts are being made on the island of Providenciales, yet are comparatively limited. Glass is collected and crushed, and to a limited extent, paper products are bailed and exported. Informal metal scavenging takes place, largely for copper and aluminum.

Poaching

The poaching of marine products is a significant threat to the environment of the Turks and Caicos, and is conducted on many levels.

The area of poaching that’s of most concern in the Turks and Caicos is commercial fishing conducted by Dominican fishermen. The typical practice is that larger diesel commercial vessels enter Turks and Caicos waters and operate with fleets of relatively small tender boats, which are often equipped with air compressors. A very broad range of marine products is typically collected, including parrotfish, sharks, lobster, and nearly all types of scale and fin fish that can be speared. There have been cases of vessels captured with thousands of pounds of parrotfish, in addition to vast quantities of other species.

Smaller scale yet still impactful poaching of marine animals takes place throughout the Turks and Caicos. As the archipelago isn’t extensive, heavy fishing at certain locations can set back populations to the point where it may take decades for any hope of recovery. Examples include conch habitats in seagrass beds in the Bight in the Princess Alexandra National Park and in the Northwest Point Marine National Park. A decade or two ago, these locations had thriving conch populations, yet despite being protected areas where fishing is illegal, conch has essentially disappeared.

Organizations and Associations

The Turks and Caicos is home to several organizations that strive to protect, preserve, restore, and bring awareness to environmental conservation issues in the islands.

The Turks and Caicos National Trust

The Turks and Caicos National Trust is an organization that preserves natural and historical sites in the Turks and Caicos, often with the goal of making them accessible to residents and visitors. The National Trust oversees such sites as Cheshire Hall Plantation and Wades Green Plantation, Conch Bar Caves, and Bird Rock Trail.

The National Trust often works with international organizations to further conservation work, including the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), and the San Diego Zoo.

Turks and Caicos Reef Fund

An often-underappreciated organization is the Turks and Caicos Reef Fund, a non-profit dedicated to preserving and fostering the marine environment in the Turks and Caicos through conservation work, education, and installation of features such as mooring for tourism industry vessels.

The Turks and Caicos Reef Fund has been leading the response to the stony coral tissue loss disease in the country, and initiated the topical antibiotic treatments to coral heads, which has been suggested to be the most effective response.

Government Departments

Regarding enforcement of laws and regulations pertaining to the environment in the Turks and Caicos, several different departments have the purview of enforcement.

Department of Environment and Coastal Resources (DECR)

The Department of Environment and Coastal Resources bears the responsibility for many of the issues relating to the environment, including oversight of protected areas, oversight of beaches and the marine environment, much of the practical licensing relating to water sports and charter companies, as well as many other environmental concerns.

Planning Department

The Turks and Caicos Planning Department is responsible for most issues pertaining to development, including illegal development, clear-cut bulldozing, and many aspects of the environmental impact of development and construction, and has involvement in the adaption of broader development plans, including the National Development Plan.

Environmental Health Department

The Environmental Health Department oversees some issues relating to pollution. Problems such as hydrocarbon and chemical dumping and pollution are under the purview of this department.

Royal Turks and Caicos Islands Police Force

The Royal Turks and Caicos Islands Police Force typically has the duty of enforcing littering and dumping laws, and issuing tickets.

The Marine Branch of the police force deserves the credit for seizing the majority of vessels caught poaching in the Turks and Caicos, especially those of Dominican origin.

Department of Agriculture

The Turks and Caicos Department of Agriculture, which includes the office of the Chief Veterinarian, in theory would oversee issues such as the euthanasia of invasive animals, and controls on the importation of potentially invasive species.

Protection of New Areas in the Turks and Caicos

Perhaps one of the most effective strategies when it comes to preserving and protecting the environment in the Turks and Caicos is identifying additional areas that should be protected, and preserving the area either publicly or privately.

There are many examples of areas that deserve to be protected, and the following are worthy considerations.

Mudjin Harbour, Juniper Hole, and the Crossing Place Trail

Mudjin Harbour, one of the most popular attractions in the Turks and Caicos and often cited as being the most scenic spot in the country, is actually not protected, and much of the coast has been parceled up for development. In 2021, a deal was reached by the government to repurchase much of the north-western section of the Crossing Point Trail and Juniper Hole coastline, as the region was sold by a past administration under very dubious circumstances, with repurchase by the government at a relatively minor sum agreed to by both parties as a settlement to legal issues raised. Unfortunately, ideas are being floated to develop a resort on the coast, rather than preserve it for recreational, tourism, and conservation reasons.

The coast at the famous Mudjin Harbour overlook and Dragon Cay has already seen development, including an imposing restaurant, and will likely see quite a bit of more development going forward.

East Caicos

East Caicos is one of the largest uninhabited islands in the region, and nearly all of the rare and endemic plants of the Turks and Caicos are extant on the island. Geologists, botanists, ornithologists, and scientists focusing on anchialine biodiversity have expressed great interest in the island, and concerns have been raised that any development could have broad impacts.

East Caicos supports an interesting array of fauna, including feral donkeys that were introduced to transport cave guano and sisal via railroad, the native Turks and Caicos boas, and the Turks and Caicos Rock Iguana, which may have become re-established on the island from populations on nearby Iguana Cay.

East Caicos is also known to be one of the few spots where the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) and West Indian whistling duck (Dendrocygna arborea) can be consistently seen, and the north-eastern coast beach on the island is one of the few known turtle nesting beaches in the Turks and Caicos.

Cedar Point, Dickish Cay, and Joe Grant Cay

A highly-scenic section of the Turks and Caicos spans the water and cays between Cedar Point and East Caicos, including Dickish Cay and Joe Grant Cay, and this area could be invaluable to the future tourism industry on Middle Caicos for several reasons.

Foremost is simply the natural beauty of the cays, ocean, sandbars, and reef in the area, yet something that may not be broadly appreciated is that these relatively sheltered bays and cays essentially will be the primary tourism and recreational vessel destination for trips from Middle Caicos, and will be to Middle Caicos what Little Water Cay, Half Moon Bay, Water Cay, and Fort George Cay are to Providenciales. Middle Caicos simply doesn’t have many feasible destinations to visit by boat, especially when there is much of an ocean swell.

A new nature reserve or national park at the cays east of Middle Caicos could also include the historical site of Jacksonville, and several of the dry cave systems on East Caicos, which would further add to the diversity of the protected area.

Plandon Cay, Middle Creek Cay, and McCartney Cay

To the North of South Caicos and south of East Caicos are a system of small cays and channels, collectively comprising one of the most scenic areas in the Turks and Caicos. Natural beauty aside, the coastal region supports a very diverse range of bird and marine life. The area includes Plandon Cay, Middle Creek Cay, McCartney Cay, Sand Bore Cay, Big Cay, and Sail Rock Island. The channels between the cays support some of the largest numbers of sharks of any close coastal location, and a wide diversity of birdlife is present.

From the recreational perspective, the general area is perhaps the best birdwatching, flats fishing, and DIY coastal fishing location in the country, and an exceptional kayaking, paddleboarding, and kiteboard setting, and the tourism potential and benefit to the South Caicos economy is likely great.

Water Quality Concerns

Another area of environmental concern in the Turks and Caicos is water quality, both of marine and freshwater lenses.

In the Turks and Caicos, most water quality data pertains to the marine environment, rather than the limited fresh and brackish water lenses found on some of the islands. Eutrophication appears to be increasing at a few select spots in the county, particularly at a few sheltered spots along the northern coast of Providenciales, including directly west of the popular Bight Reef (Coral Gardens) beach snorkeling site. This effect may be caused by enriched sewage and landscaping water runoff from development.

Another point of contention is dredging, and its impacts on reefs, seagrass beds, and marine life. The Turks and Caicos over the years has seen a significant variance in what types of coastal engineering works are granted approval, and project approvals are likely impacted by changes in government administrations and public sentiment.

It’s difficult to measure the impact to reefs and seagrass beds caused by dredging. Turbidity and sediment suspension and deposition can be measured, yet data that differentiates the impacts caused by dredging from those caused by tropical storms and hurricanes is limited. In any case, the turbidity and sediment deposition after Hurricane Irma and Hurricane Maria in 2017 were some of the highest levels ever recorded around Providenciales, and Leeward Going Through Channel had accumulations of nearly 24” (60 cm) of fine particulates at some locations.

Very little research or concern is directed to the freshwater lenses in the Turks and Caicos, likely due to their limited extent and limited value to development and tourism. In the past, wells were located near most communities in the country, and were depended on for life. Water quality and salinity varied greatly, with the wells near Kew on North Caicos being broadly considered to be the best and most reliable, and those on Providenciales only offering brackish water that caused dental issues. Today, reverse osmosis desalinated water and collected rainwater have almost entirely displaced well use for anything other than landscaping. Landscaping and agriculture overuse and abuse, and sewage leaching have largely made well water in many areas unusable for human consumption without prior reverse osmosis purification, exemplified by the inland Grace Bay lenses, which were once the best on Providenciales, yet now have salinity in the thousands of PPM.